'Surfari' by Tim Baker - a review

One of the conversations I increasingly hear amongst surfers - in the surf, in magazines, online - is how to continue to include regular

(ie. daily) surfing into lives that include family, work and the inescapable

aging process. For many years, it has been surfing women who have sacrificed waves in order to have and raise a family, to keep house, to look

after others, and often to build a career. While many men-folk of past days shared (most especially) the

questions regarding work, they did not always have the same level of household demands and

expectations as women - cleaning, laundry, planning and preparing meals, childcare, organising family events. Certainly, some men did take these roles on, but most were not expected to. But now men moving into their 30s and 40s are shouldering these responsibilities more than ever and so are wondering how they are going to continue a version of the lifestyle of

their youth into middle-age. While men today do not necessarily begrudge

their increasing obligations to relationships, housekeeping and childcare, it does involve a

lot of compromise and they are looking to each other to share

their fears, mistakes and triumphs regarding all this.

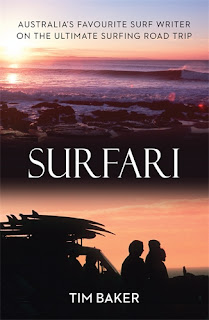

In this space, Tim Baker’s recently released book, Surfari (2011), is a timely and

contemporary surfing story for this growing number for men whose

high-performance, free-wheeling, travel-filled, shortboard surfing days are

increasingly negotiated by family, work, the aging process and myriad other

concerns and commitments. Tackling these questions himself, Tim enlists the

support of his wife, Kirsty, to take their children with them on a driving trip around Australia. This trip is Tim’s effort to find a balance between family and

surfing, and he has several hoped-for goals including: to explore and

learn more about the country he grew up in; to live out a teenage dream of

living a surfing life without the constraints, stress and daily-grind of

timetabled work; and to include his family this journey and share the experiences

together.

The resulting book gives him a lovely opportunity to write into

existence the role that family, friends, partners, wives, children, ageing and

work play in the way our surfing lives progress and develop, shift and change. To

date, this is still a rare tale. I mean, how often are wives and children included in representations of long and adventurous surf trips? There could certainly be

more, but off the top of my head, I can only recall Mick Waters’ wonderful 2009

film, Little Black Wheels, doing this

to any degree. However, Surfari is a

reflection on the ways that we can include the people we love in our surfing lives,

and how this can ultimately add to our experiences. Having said that, even in

this around-Australia account few women appear as surfers, other

than as wives, girlfriends or daughters. Maybe they just aren’t

there? But to me (of course) their absence stood out. The excellent exception comes in the form of the young Macaulay women, Ellie,

Laura and Bronte, who have been brought up surfing WA’s wild coastline with

their parents, and who are well-known as fearless and curious surfers. How will

they tackle questions about balancing surfing and family life as they grow? How

will they move through their lives, keeping surfing as a part of their everyday

(or not)? Perhaps Tim might have found some answers to his own questions there, or at least some solidarity?

Throughout Surfari,

Tim’s admission of his fears – not only about family, but also of some waves,

of isolation, injury and sharks – were refreshing. Voicing such concerns can be

quickly labelled as shameful cowardice, especially in surfing cultures, so it

takes guts to openly admit that the fantasy of surfing alone can, in reality,

carry other internal obstacles. Tim’s internal dialogue was refreshingly

honest and often spontaneous, as though he chose not to think too much about

the risk of publishing it. However, it was this same kind of introspection and

self-reflection that I found to be one of the frustrating things over the

course of the book. Many of Tim’s chapters begin or end with tortured

lamentations about the difficulties of finding the balance he seeks between

surfing and family, of making room for everyone, of fulfilling everybody’s

needs. The easy solution seems to stop

worrying about his family, stop caring, but he does care.

And therein lies the dilemma.

I felt Tim was too hard on himself. care and commitment

to those he loves is what makes him different from some of the characters he

meets along the way – heart-broken, lost, estranged from loved ones, and finding peace by immersing themselves in a solitary and isolated surfing life where nothing much

matters except the swell. But some of Tim's soul-searching could have been sacrificed to allow for more inclusion of other perspectives – those of

his family perhaps. His wife Kirsty, and their children are bound up in Tim’s

journey, so it would have been great to hear accounts from them about Tim’s

dilemma - about how they feel about

his surfing, and how they feel about being so deeply considered as a part of

it. In particular, Kirsty and daughter Vivi, are central players in making room

in their lives for Tim’s ideas and aspirations, and while I don’t think this is

a terrible thing – that is after all, the nature of family – it would have

added a richness to this book that might have spoken to many surfers of Tim’s

ilk, as well as their families. I also found myself wondering how and whether

Tim’s kids are interested in sharing waves with their dad and how this itself

becomes a newly explored part of Tim’s surfing life, by negotiating the types

of waves he can access to share with his kids and their possible desire to

accompany him on his surf jaunts. I’m sure the parents of the young Macauley women

have much experience and wisdom to share on that particular topic.

I know a

number of 30 and 40-something guys who are embarking on or planning a similar

trip with their families, and I have recommended Surfari

to each of them. There are certainly things that grated (like the pervasive

product placement of the sponsoring companies, who made the trip affordable but

which became a bit exhausting), things that became repetitive (the ongoing

branding of Tim Winton as the only writer of the West Australian coastal landscape.

What about Robert Drewe? Brett D’Arcy?), and there also are the obvious and

unavoidable issues surrounding Tim’s often open discussions and descriptions of

places and breaks. There have been high levels of emotion following his

publication of this book, both online and in print. Tim has a particular

history in surf media, which means that many people have a historical distrust

or loathing of his past and present editorial and writing decisions. I have

heard him condemned for his readiness to locate waves and, even more taboo, to

provide even vague directions to them. I do understand those irritations and the passionate anger

that accompanies them, but I’m not quite sure how I feel about all of that. As

a daughter of a particularly famous and much-visited surf town, I have a

similar relationship as Tim to the thick and competitive crowds of visitors to our

much photographed and promoted (by surf media) home breaks in south east Queensland

and north east New South Wales. In my experience, surfers from the kinds of

‘secret’ breaks that Tim describes would happily come to our already busy home

breaks and paddle into whatever wave they chose, so I always feel there is a

certain level of hypocrisy and selfishness in the entitlement to localism and

protectiveness at their own breaks. But then, I also live the repercussions for

long-term promotion and over-exposure, so I absolutely understand their fears and concerns, and would not wish wholesale development and growth upon their communities.

These questions and critiques are only made because I think Surfari has so much merit and that it will occupy a timely place in the lives of many men who surf. But in the end, it depends on what you decide to take from Surfari – an unwelcome map to a number

of Australian surf breaks, or a thoughtful and personal consideration of the

concerns of someone attempting to continue to surf as much as possible, while prioritising his

relationships to loved-ones. I choose the latter. It’s a tough topic, and I

doubt Tim would claim to offer any answers beyond admitting the difficulty and

sacrifice of all of this, while advocating for the joy to be found from sharing your surfing life with your family. But taking the risk to think and write about it,

is something that will and should resonate with many surfers.

Thanks for taking the time to write such a thoughtful book review.I think the surf publishing arena is fraught.There are a lot of bases to cover and markets to consider which can/may get in the way of a more expansive tome.

ReplyDelete