Laura Crane has skin in the game: a surf story in five parts*

*The title of this essay is inspired by Kylie Maslen's recent article about women's sport, 'Skin in the Game'. The essay itself is dedicated to my friends in the Institute of Women's Surfing (Europe), with my thanks for sharing your stories and friendship and resources.

I used to consume it voraciously, reading everything I could find - every book, magazine, website, and blog. I was trying to understand it, to understand the world it was describing, to see the patterns and themes as well as the points of difference and resistance. I wasn't out to create a typology or anything like that, but to get my head around what it is that we say to ourselves as writers, editors, photographers and readers. I wanted to know who was talking and who might be reading and to know what was missing from these stories; to find the gaps.

It didn't take long for me to turn away from mainstream print magazines, in which I saw so little hope beyond repetitive versions of the 'boys and barrels and surf trips' fantasies that dominated. Yes, longboards came to be included, but not really in any interesting way, and women who were surfing remained a treat to find in the pages. The explosion of online media changed things a bit, offering different spins on things for a while. But not-paying-for-content and click-bait came to dominate, and there we find The Inertia... so that is that.

There is always excitement and hope in blogs, with the best surf writing I've ever read contained in little-noted, advertising-free websites that are a labour of love and originality. Stories of living in cities and trying to keep surfing in your life; of finding it in corner stores, the bough of a tree and cracks in the pavement. Stories of the past that don't fit with the established way of thinking about the shortboard revolution. Stories that found joy in simply catching waves, rather than being any good at it. Stories from places that weren't east coast Australia or California or Hawai'i. Stories that were cold, grey, sad, isolated and mundane. I love blogs and these stories still.

Most significantly, blogs were the spaces in which I first came to find stories by and about women that weren't cheesy fantasies that ended in some guy getting laid, or at least getting a good look at a semi-naked woman, and that weren't dependent on the support of advertising. Like the stories above, they told of surfing without an agenda, and without a sense of what couldn't be said. Because it could be said. These were stories by women, about women, for women. Men were welcome in these stories, but these stories weren't written in the over-saturated narrative arc of men's shortboard surfing. These weren't stories of babes in bikinis doing bottom turns. These weren't stories of women in distress needing rescuing. Well, sometimes they were, but they were honest and vulnerable. They were trying to make sense of their surfing lives and experiences, and to share them in a way that wasn't part of the world they knew they weren't welcome in - mainstream surf media. These sites created pockets and communities and safe spaces. They were often left untouched by the kinds of vile commenting that erupted elsewhere and which ruined so many blogs.

Mainstream surf media still carries the most credibility clout, but blogs are still the best.

But things have shifted since 2010, because now we have Instagram and it's associated world of likes and reposts and refocus on visual over written texts. Don't get me wrong, I use Instagram and find it really interesting and like it a lot. There is space for continued visibility for diverse kinds of women who surf, and certainly that has allowed me to discover images and stories of all kinds of diverse women as I scroll. I love it!

But these are not the stories that the algorithms pick up, nor are the women in these pictures the ones who get discussed in other media spaces.

The visual focus of Instagram has, so far as women and surfing are concerned, re-emphasised images of women's bodies as the key offering. This has also meant that we get a re-emphasis on particular kinds of women's bodies - hot bodies. Women might be doing a good job of showing themselves surfing, but so often, the most popular images are those of women in bikinis. And that is a key point; it's the women doing this themselves and emphasising their bodies. Poking out their butts, letting their boobs fall out the side of their bikini, sporting vulva-revealing swimmer bottoms.

Your body, your choice.

For many women, being able to make these choices is described as "empowering". The use of "empowerment" is linked to ideas of throwing off shackles of shame about females bodies and sexuality, and that's not nothing! Being rid of corsets and prohibitive volumes of fabric has been key to women's access to the workforce, to freedom of movement and participation in sports. In Australia, it has only recently been mandated in some states that girls can wear shorts and trousers to many schools instead of skirts or dresses only.

But, just because having the capacity to choose is feminist, it doesn't mean the choice itself is.

Given the idea of headless women and the male gaze, you can see how and why Roxy's 2013 campaign for their Biarritz Pro came under such fire (links to a range of responses are included via the hyperlink).

We've come some way from this - in art and in the media - but things remain imperfect. The developments we've had have been through various women's interventions and activism. Women criticised the system, took back their naked bodies, by representing themselves in new ways - looking back at the camera, staring down the male gaze. They empowered themselves and their images, by replacing men's desires with their own. Perhaps sometimes these different desires lined up, but not always.

These changes have translated to surf media too. Like the stories I described myself reading in blogs throughout the 2010s, it is women who surf having the time, space and resources to tell their own stories that has changed things. Taking and posting their own images of their own and other women's surfing bodies and lives. By starting magazines, websites and businesses of their own, a growing number of women have even managed to cut out men from final editorial control over what gets published on pages, not only on social media. The broader effects of women's activism and other civil rights and social movements meant some changes such as women getting their head and faces reattached to their bodies in advertising, and even photos of women actually surfing in mens' surf magazines. This has been exciting! But it's also had limits, and conventional female beauty and sexiness still seem to rule.

That the male gaze still often shapes how women represent themselves today should not surprise you. 'Sex sells' they tell us - but whose sex, under whose definition? When it comes to women's access to sponsorships and mainstream surf publications, men remain key gatekeepers and so the power of the male gaze lingers.

So, the story's the same but the context in which we're telling it has changed. What I'm talking about here is less about "art", than "marketing" and "branding" - about turning women into commodified consumables. We see images of naked and semi-clad women used as evidence of "empowerment", but what that really means is no so easy to understand. It might mean they personally are empowered to do what they like, or to make money from their gym-honed body, and again, I will always stand by the idea that it's your body, your choice. But in what context are those decisions being made, and to what effect?

Like so much of the art world, surf media seems to be largely stuck in a loop.

“We’re not seeing anything new,” [Hannah Gadsby] reiterates. “The art world doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Being an object, being objectified, [creates] a toxic culture, because we don’t have the same cultural influence as men do. They’ve written the story, they have the power.

“#MeToo should not be limited to art or TV. What’s happening in the world where there’s no glamour is worse. There are powerless people in the world who don’t have a voice, who are struggling in this toxic culture of silence."

None of these images is awful or messed up - they're beautiful! (I've included the one of Mick Fanning to highlight how underwater images can be gendered and to emphasise how 'women under water', like 'women in baths', tells a particular story.) But they're not interesting to me because they're images that adhere to a long tradition of European heterosexual men's ideals of female beauty. A male gaze through the past and into our present. A paleo-male gaze of no carbs, no sugar, and no indulgence. A medieval-male gaze of madonnas and whores. A Victorian-male gaze of morality, corsets and self-restraint. A hyper-sexualised male gaze of pouting lips and bare skin dressed up as empowerment.

The male gaze - or more correctly, the heterosexual male gaze - is far from a new idea. It was an idea presented in 1975 in an essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, by Laura Mulvey who worked in feminist film studies (I've provided a link in case you want to read it). Following Mulvey's work, Janice Lorek writes that,

Visual media that respond to masculine voyeurism tends to sexualise women for a male viewer. As Mulvey wrote, women are characterised by their “to-be-looked-at-ness” in cinema. Woman is “spectacle”, and man is “the bearer of the look”.

Using close-ups, the camera forces the viewer to stare at Cora’s body. It creates a mode of looking that is sexual, voyeuristic, and associated with the male protagonist’s point-of-view. ... A lifetime of seeing women sexualised in television, music videos and advertisements has made us very comfortable with assuming the male gaze.

As so many artists, photographers and Instagram user show us, just because women are in photos of them wearing cute underwear or looking great or posing in swimmers doesn't mean they're defined by this gaze - that's in the motivation and framing of the shots.

More specifically, an interview Stab published with British surfer, reality TV star and model, Laura Lou Crane, titled, 'Laura Crane is Empowered'.

I wasn't going to link to the article itself, because I didn't want to electronically tether myself to them. But given that I'd like to have things here as an archive and a resource, I'm going to. No judgement if you do click on it, as I had to look at it a bunch of times myself to write this (what was never meant to be an) essay. There's really no need, though, because if you've ever read a Stab interview with a woman before, you pretty know what it says and does. In sum, Stab uses their interview question to justify their super sexual images of Crane as well as working to make her complicit in her own sexualisation. They get to her to talk about how beautiful the shoot made her feel.

In the world of Stab's treatment of women, this tactic of making women complicit in sexualising themselves in line with the hetero male gaze, is not new. Eight years ago, Stab published what I would position as a game-changing essay in which they got Laura Enever to talk about how empowering she experienced the photo shoot as being. The article was called 'The Devil in Miss Enever'.

Enever was 19 and developing a profile and trying to get and keep sponsors and she was new to these kinds of shoots and they asked her questions on the record that they knew she would answer in certain ways and over which they had editorial control anyway.

None of the high-salaried men or women surfers are ugly. Is that a bad thing? Is it so wrong to be employed to sell boardshorts and bikinis? And, has your gal-next-door beauty been a thrill to your sponsor? Marketability is everything. It sucks, kinda, but it’s a market. It’s about selling. It’s sad when great surfers don’t get sponsors, though. Sexiness sells. I think about Maria Sharapova and how she was the sexiest girl in tennis. I didn’t follow tennis, but I knew Maria Sharapova because of her sexiness. She did so well for herself because she was sexy and confident and she was an amazing athlete. That’s what it comes down to.

Were you specifically warned about the Stab shoot? That we were devils? (Laughter detonates) I was! I was! I heard from Alana (Blancahrd) and Bruna (Schmitz) who you did the photo shoot with last year. They told me how they were freaked out about how you, like, tried to get them naked. I’d been warned a few times, but it’s fine, because you guys are a men’s magazine and it’s an amazing magazine. At the shoot, I was told my first couple of photos weren’t sexy enough and that I had to take some clothes off, but it ended up being really cool. If we thought the photos were degrading or didn’t suit my image, I wouldn’t agree to have ‘em run.

We adore women! The shots you did of Alana and Bruna are so beautiful and they’re so sexy and I heard the photos that Steph Gilmore didn’t get run look amazing! We want to show how sexy and feminine girl’s surfing is. Stab is helping us out by running us alongside models. It’s just really cool. (Laughing) Here’s something. I was surfing P-Pass with Steph Gilmore and we were talking about how fun it would be to, and this is six-foot perfect P-Pass barrels, to take our tops off and get totally pitted, and how that would be the cover of Stab! Topless! But, we didn’t have the guts.

Enever's answers and the accompanying shots always make my stomach turn. I show them in my sport sociology and gender studies classes to make the same point that I'm making in this discussion. The thing is, Enever clearly understands the system she's operating in and that she can get ahead using her looks, her body. She knows it and she is pretty and hot, so she's decided to run with it. But she also knows and explains that not all women will get ahead in this male-defined way of doing things, which is "sad" for some women but it's also okay because she can take advantage of it. She's fully complicit in the continuation of the power of the hetero male gaze in defining women's representations in (some) surf media, as well as in who gets sponsorship or not. I understand Enever was (is?) a young, vulnerable player here, really I do! But the degree of understanding she shows and is comfortable with, has never stopped feeling shocking to me.

But Enever suggests it's not just her who had to negotiate decisions in a Stab photoshoot. She describes how other women who surf had warned her about the behaviour of men on photoshoots for this magazine, about how "they were freaked out" about the degree to which they were sexualised. And yet, Alana and Bruna continue to pose for Stab, and to profit from allowing the magazine to sexualise them. The fictional 'at home with' style shoot Alana Blanchard made with her partner Jack Freestone is an incredible example of how the male gaze works - a voyeuristic fantasy about who the male editors and their readers want to be and who they want. The stylists and photographers are following a 1950s type of white, heteronormative, gendered domesticity - Jack is clothed and lounging, Alana is a scantily-clad housewife. It's so... lame.

And here we find Laura Lou Crane, fresh from her celebritising stint on the reality TV show, Love Island. In this series of images (shot by, it seems, a woman) and interview (with a man), Crane comes across as vulnerable and fragile. Alongside the images of her in small pieces of lace, PVC and ill-fitting lycra, she briefly talks about her struggle with bulimia, while at the same time highlighting the pressures that caused it - namely, the pressures of being a young woman surfing and modelling in "that industry". This is highlighted in the pull-out quotes Stab uses:

Being a surfer and traveling the world and modeling put all these pressures on me as a girl growing up in that industry. Which, don’t get me wrong, it is an amazing way to grow up, but it does weigh on you.

The questions asked of the women have changed since those days with Laura. In this interview, as in others, they're much less explicit in getting Crane to justify Stab's style and sexualisation of women, but that might be because there is a new script that women know to keep to - to talk about feeling empowered through sexualising themselves. But even when the interviews themselves focus on women's surfing lives (as did the interview with Imogen Caldwell), the images remain firmly defined by sex.

I took some screenshots of the Instagram story Stab used to promote and distribute the article. (For the record, I don't follow them.)

The contradictory links Crane makes between the impact on Instagram on her and her resulting bulimia, and then her lack of reflection on her own role in promoting sexy, feminine, idealised, female bodies on social media is, well, alarming! She clearly understands the impacts of social media on body image and mental health, and yet, because she feels as though she's come through it, she makes no attempt to protect anyone else from the same pressures.

Her body, her choice. But don't expect me to respect her choice.

But here it is - empowerment - apparently being taken up by the many folk commenting on Crane's Instagram post about the interview (you can find the post and comments here):

Commenters focus on this story as inspiring and empowering and on Crane as a role model for young people, especially young women and men. Her body is discussed at length as both a recovered bulimic body and a sexy body, and is celebrated for being "sporty" and "different" than super thin models. But I'm just not so sure; as I've argued before, diversity is not a white woman, and while not being thin to an emaciated degree might feel different, Crane is still slim, toned, feminine, and young - the ideal of the male gaze.

But...

While in this (very long) discussion I'm holding Crane accountable for her choices, it's still Stab that I'm repulsed by and who I'm railing against. The interview title, 'Laura Crane is empowered' is poking fun people who they know will be frustrated by the images and interview. The common rebuttals they will likely offer sit along the lines of "Don't look then", or "you're just jealous" or "femi-nazi". The idea of "don't look" is fair enough, except that it's stupid - it's online, it's available, it's part of my surfing cultural orbit. And anyway, I'm not so much concerned about me and mine as I am about the men who do look at these magazines and ogle the women on the pages, and comment on their bodies and ideas. (Although, to give them some credit, Stab didn't open the comments thread under this interview, which I was super pleased to see.)

Even worse, critics of my critique accuse me of being a bad feminist or anti-women. But I'm not. I just don't buy the idea that making money by letting faceless men take pleasure from my body is in anyway helpful to the majority of women. A couple of years ago, Hadley Freeman wrote a great article in The Guardian about changing notions of "empowerment":

The problem with this approach is that it leads to a great big pile of nothing. The suggestion that women should unthinkingly celebrate one another purely out of sisterly feeling is about as patronising as the idea that women shouldn’t trouble their brains with opinions. ... Empowerment has become the cover for doing whatever the hell you like. It is a self-created safe space: as long as you say you are empowered, anyone who complains is trying to oppress you. ... But the biggest irony about empowerment is not just how utterly meaningless – disempowered, I guess – it has become as a term, but how those who claim to feel it and those to whom it is sold are the ones who need it least. It is no surprise that I see so many adverts promising empowerment, because I am precisely the kind of person to whom empowerment is now marketed: white, thirtysomething, educated, middle class with disposable income. I don’t need to be empowered anymore than Kardashian does. Only those already in possession of quite a lot of power would feel empowered by leggings, or a TED talk, or naked selfies. Empowerment has become not only a synonym for self-indulgent narcissism, but a symbol of how identity politics can too often get distracted by those with the loudest voices and forget those most in need of it.

Freeman cites an NY Times article by Jia Tolentino, who writes that:

Sneakily, empowerment had turned into a theory that applied to the needy while describing a process more realistically applicable to the rich. The word was built on a misaligned foundation; no amount of awareness can change the fact that it’s the already-powerful who tend to experience empowerment at any meaningful rate. Today “empowerment” invokes power while signifying the lack of it. It functions like an explorer staking a claim on new territory with a white flag.

Less than 24 hours ago, when I sat down to start writing, I thought I would write a quick 500 words that would summarise what I was thinking and feeling. But it wasn't possible. And I’m not pleased about so clearly using the examples I have of specific women - I’m not usually one to do that. Instead, usually, I talk about the system in which those women are making their choices and I’ve certainly done that here too. But at the same time, with the examples I use here I couldn't avoid that the women in these images are making the choice to sexualise their own bodies and to claim it as empowerment. That’s their choice, but they’re doing it with seemingly clear knowledge of the system in which they’re making their choices, including an understanding that not all women are able to gain benefits from such practices and thus, they’re complicit in things being harder for women who don’t look like them. Not for a moment would I suggest that was their intention! But nonetheless, many girls and young women seem to look up to sexualisation and lingerie shoots as aspirational and inspirational and role models for how to make it as surfers - that is the effect.

Laura Lou Crane - and Laura Enever and Alana and all of the women I'm discussing here - deserves better than what is on offer for her via Stab. She really does. But the many people who consume the product she's presenting as empowerment deserve better too - and I include boys in that.

The main thing I learned in my PhD research about women and surfing was the politics that the women I spoke with operated by, which is rooted in a feeling of solidarity with other women and can be summarised very simply; whatever you do to get waves in the surf, don't make things harder for other women.

I. Oh hey, surf media!

Surf media is such an interesting world.I used to consume it voraciously, reading everything I could find - every book, magazine, website, and blog. I was trying to understand it, to understand the world it was describing, to see the patterns and themes as well as the points of difference and resistance. I wasn't out to create a typology or anything like that, but to get my head around what it is that we say to ourselves as writers, editors, photographers and readers. I wanted to know who was talking and who might be reading and to know what was missing from these stories; to find the gaps.

It didn't take long for me to turn away from mainstream print magazines, in which I saw so little hope beyond repetitive versions of the 'boys and barrels and surf trips' fantasies that dominated. Yes, longboards came to be included, but not really in any interesting way, and women who were surfing remained a treat to find in the pages. The explosion of online media changed things a bit, offering different spins on things for a while. But not-paying-for-content and click-bait came to dominate, and there we find The Inertia... so that is that.

There is always excitement and hope in blogs, with the best surf writing I've ever read contained in little-noted, advertising-free websites that are a labour of love and originality. Stories of living in cities and trying to keep surfing in your life; of finding it in corner stores, the bough of a tree and cracks in the pavement. Stories of the past that don't fit with the established way of thinking about the shortboard revolution. Stories that found joy in simply catching waves, rather than being any good at it. Stories from places that weren't east coast Australia or California or Hawai'i. Stories that were cold, grey, sad, isolated and mundane. I love blogs and these stories still.

Most significantly, blogs were the spaces in which I first came to find stories by and about women that weren't cheesy fantasies that ended in some guy getting laid, or at least getting a good look at a semi-naked woman, and that weren't dependent on the support of advertising. Like the stories above, they told of surfing without an agenda, and without a sense of what couldn't be said. Because it could be said. These were stories by women, about women, for women. Men were welcome in these stories, but these stories weren't written in the over-saturated narrative arc of men's shortboard surfing. These weren't stories of babes in bikinis doing bottom turns. These weren't stories of women in distress needing rescuing. Well, sometimes they were, but they were honest and vulnerable. They were trying to make sense of their surfing lives and experiences, and to share them in a way that wasn't part of the world they knew they weren't welcome in - mainstream surf media. These sites created pockets and communities and safe spaces. They were often left untouched by the kinds of vile commenting that erupted elsewhere and which ruined so many blogs.

Mainstream surf media still carries the most credibility clout, but blogs are still the best.

But things have shifted since 2010, because now we have Instagram and it's associated world of likes and reposts and refocus on visual over written texts. Don't get me wrong, I use Instagram and find it really interesting and like it a lot. There is space for continued visibility for diverse kinds of women who surf, and certainly that has allowed me to discover images and stories of all kinds of diverse women as I scroll. I love it!

But these are not the stories that the algorithms pick up, nor are the women in these pictures the ones who get discussed in other media spaces.

The visual focus of Instagram has, so far as women and surfing are concerned, re-emphasised images of women's bodies as the key offering. This has also meant that we get a re-emphasis on particular kinds of women's bodies - hot bodies. Women might be doing a good job of showing themselves surfing, but so often, the most popular images are those of women in bikinis. And that is a key point; it's the women doing this themselves and emphasising their bodies. Poking out their butts, letting their boobs fall out the side of their bikini, sporting vulva-revealing swimmer bottoms.

Your body, your choice.

For many women, being able to make these choices is described as "empowering". The use of "empowerment" is linked to ideas of throwing off shackles of shame about females bodies and sexuality, and that's not nothing! Being rid of corsets and prohibitive volumes of fabric has been key to women's access to the workforce, to freedom of movement and participation in sports. In Australia, it has only recently been mandated in some states that girls can wear shorts and trousers to many schools instead of skirts or dresses only.

But, just because having the capacity to choose is feminist, it doesn't mean the choice itself is.

II. The boys who watch the girls go by: The (heterosexual) male gaze

The male gaze is an important way of understanding how women have been and often still are represented in images across all kinds of art and media, and why you might feel uncomfortable, aroused or removed when you look at images of naked or near naked women. 'The male gaze' refers to hierarchies of who got to speak and be heard, of who received money, power and fame, of who was the artist and who was the model. That is, the idea of the male gaze takes into account how men's art and images have dominated and defined representations of women. The idea outlines that under the male gaze, women become objects to be consumed and enjoyed; they're naked; they can be looked upon but never touched; they lose their faces, eyes, and agency, their own gaze excluded from view. In art we see this in naked bodies with faces turned away, or reclining with legs open to the viewer. In surf magazines, this has been replicated in images of semi-clad women with no faces nor, often, even heads! Just young, slim, sexually available female bodies of the kind desired by men, and then with their faces removed.Given the idea of headless women and the male gaze, you can see how and why Roxy's 2013 campaign for their Biarritz Pro came under such fire (links to a range of responses are included via the hyperlink).

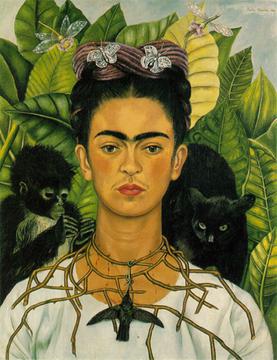

We've come some way from this - in art and in the media - but things remain imperfect. The developments we've had have been through various women's interventions and activism. Women criticised the system, took back their naked bodies, by representing themselves in new ways - looking back at the camera, staring down the male gaze. They empowered themselves and their images, by replacing men's desires with their own. Perhaps sometimes these different desires lined up, but not always.

|

| Frida Kahlo, 'Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird' (1940) |

These changes have translated to surf media too. Like the stories I described myself reading in blogs throughout the 2010s, it is women who surf having the time, space and resources to tell their own stories that has changed things. Taking and posting their own images of their own and other women's surfing bodies and lives. By starting magazines, websites and businesses of their own, a growing number of women have even managed to cut out men from final editorial control over what gets published on pages, not only on social media. The broader effects of women's activism and other civil rights and social movements meant some changes such as women getting their head and faces reattached to their bodies in advertising, and even photos of women actually surfing in mens' surf magazines. This has been exciting! But it's also had limits, and conventional female beauty and sexiness still seem to rule.

That the male gaze still often shapes how women represent themselves today should not surprise you. 'Sex sells' they tell us - but whose sex, under whose definition? When it comes to women's access to sponsorships and mainstream surf publications, men remain key gatekeepers and so the power of the male gaze lingers.

So, the story's the same but the context in which we're telling it has changed. What I'm talking about here is less about "art", than "marketing" and "branding" - about turning women into commodified consumables. We see images of naked and semi-clad women used as evidence of "empowerment", but what that really means is no so easy to understand. It might mean they personally are empowered to do what they like, or to make money from their gym-honed body, and again, I will always stand by the idea that it's your body, your choice. But in what context are those decisions being made, and to what effect?

Like so much of the art world, surf media seems to be largely stuck in a loop.

“We’re not seeing anything new,” [Hannah Gadsby] reiterates. “The art world doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Being an object, being objectified, [creates] a toxic culture, because we don’t have the same cultural influence as men do. They’ve written the story, they have the power.

“#MeToo should not be limited to art or TV. What’s happening in the world where there’s no glamour is worse. There are powerless people in the world who don’t have a voice, who are struggling in this toxic culture of silence."

|

| Via @artlove on Instagram |

Gadsby's point that we should 'Stop watching women have baths' - a recurring motif in art - has resonated with me. Over the last few years, I've noticed the increased series of images in surf media that I like to call 'women under water'. Women under water are naked or semi-clad, long and languorous, graceful, slim, usually white, and rarely looking at the camera. They might be diving under a wave, reaching out to a dolphin or shark, or letting a manta ray caress their naked body. [Which is a bit inter-species erotica for my taste, but then, this is not the first time such images have been produced so perhaps I'm a prude?] Sometimes these images are brave and interesting, but so often, they're not.

Image by @perrinjames via @changingtidesfoundation

Image by @maliamurphy via @oceanfilmfestival

Image by @theroadsoad via @worldsurflols

None of these images is awful or messed up - they're beautiful! (I've included the one of Mick Fanning to highlight how underwater images can be gendered and to emphasise how 'women under water', like 'women in baths', tells a particular story.) But they're not interesting to me because they're images that adhere to a long tradition of European heterosexual men's ideals of female beauty. A male gaze through the past and into our present. A paleo-male gaze of no carbs, no sugar, and no indulgence. A medieval-male gaze of madonnas and whores. A Victorian-male gaze of morality, corsets and self-restraint. A hyper-sexualised male gaze of pouting lips and bare skin dressed up as empowerment.

The male gaze - or more correctly, the heterosexual male gaze - is far from a new idea. It was an idea presented in 1975 in an essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, by Laura Mulvey who worked in feminist film studies (I've provided a link in case you want to read it). Following Mulvey's work, Janice Lorek writes that,

Visual media that respond to masculine voyeurism tends to sexualise women for a male viewer. As Mulvey wrote, women are characterised by their “to-be-looked-at-ness” in cinema. Woman is “spectacle”, and man is “the bearer of the look”.

Using close-ups, the camera forces the viewer to stare at Cora’s body. It creates a mode of looking that is sexual, voyeuristic, and associated with the male protagonist’s point-of-view. ... A lifetime of seeing women sexualised in television, music videos and advertisements has made us very comfortable with assuming the male gaze.

As so many artists, photographers and Instagram user show us, just because women are in photos of them wearing cute underwear or looking great or posing in swimmers doesn't mean they're defined by this gaze - that's in the motivation and framing of the shots.

III. She's got the power?

So this is a long way of getting into something that was pointed out to me last night, and which really really bothered me. Or, really, which continues to really bother me: the men's surf magazine, Stab.More specifically, an interview Stab published with British surfer, reality TV star and model, Laura Lou Crane, titled, 'Laura Crane is Empowered'.

I wasn't going to link to the article itself, because I didn't want to electronically tether myself to them. But given that I'd like to have things here as an archive and a resource, I'm going to. No judgement if you do click on it, as I had to look at it a bunch of times myself to write this (what was never meant to be an) essay. There's really no need, though, because if you've ever read a Stab interview with a woman before, you pretty know what it says and does. In sum, Stab uses their interview question to justify their super sexual images of Crane as well as working to make her complicit in her own sexualisation. They get to her to talk about how beautiful the shoot made her feel.

In the world of Stab's treatment of women, this tactic of making women complicit in sexualising themselves in line with the hetero male gaze, is not new. Eight years ago, Stab published what I would position as a game-changing essay in which they got Laura Enever to talk about how empowering she experienced the photo shoot as being. The article was called 'The Devil in Miss Enever'.

Enever was 19 and developing a profile and trying to get and keep sponsors and she was new to these kinds of shoots and they asked her questions on the record that they knew she would answer in certain ways and over which they had editorial control anyway.

None of the high-salaried men or women surfers are ugly. Is that a bad thing? Is it so wrong to be employed to sell boardshorts and bikinis? And, has your gal-next-door beauty been a thrill to your sponsor? Marketability is everything. It sucks, kinda, but it’s a market. It’s about selling. It’s sad when great surfers don’t get sponsors, though. Sexiness sells. I think about Maria Sharapova and how she was the sexiest girl in tennis. I didn’t follow tennis, but I knew Maria Sharapova because of her sexiness. She did so well for herself because she was sexy and confident and she was an amazing athlete. That’s what it comes down to.

Were you specifically warned about the Stab shoot? That we were devils? (Laughter detonates) I was! I was! I heard from Alana (Blancahrd) and Bruna (Schmitz) who you did the photo shoot with last year. They told me how they were freaked out about how you, like, tried to get them naked. I’d been warned a few times, but it’s fine, because you guys are a men’s magazine and it’s an amazing magazine. At the shoot, I was told my first couple of photos weren’t sexy enough and that I had to take some clothes off, but it ended up being really cool. If we thought the photos were degrading or didn’t suit my image, I wouldn’t agree to have ‘em run.

We adore women! The shots you did of Alana and Bruna are so beautiful and they’re so sexy and I heard the photos that Steph Gilmore didn’t get run look amazing! We want to show how sexy and feminine girl’s surfing is. Stab is helping us out by running us alongside models. It’s just really cool. (Laughing) Here’s something. I was surfing P-Pass with Steph Gilmore and we were talking about how fun it would be to, and this is six-foot perfect P-Pass barrels, to take our tops off and get totally pitted, and how that would be the cover of Stab! Topless! But, we didn’t have the guts.

Enever's answers and the accompanying shots always make my stomach turn. I show them in my sport sociology and gender studies classes to make the same point that I'm making in this discussion. The thing is, Enever clearly understands the system she's operating in and that she can get ahead using her looks, her body. She knows it and she is pretty and hot, so she's decided to run with it. But she also knows and explains that not all women will get ahead in this male-defined way of doing things, which is "sad" for some women but it's also okay because she can take advantage of it. She's fully complicit in the continuation of the power of the hetero male gaze in defining women's representations in (some) surf media, as well as in who gets sponsorship or not. I understand Enever was (is?) a young, vulnerable player here, really I do! But the degree of understanding she shows and is comfortable with, has never stopped feeling shocking to me.

But Enever suggests it's not just her who had to negotiate decisions in a Stab photoshoot. She describes how other women who surf had warned her about the behaviour of men on photoshoots for this magazine, about how "they were freaked out" about the degree to which they were sexualised. And yet, Alana and Bruna continue to pose for Stab, and to profit from allowing the magazine to sexualise them. The fictional 'at home with' style shoot Alana Blanchard made with her partner Jack Freestone is an incredible example of how the male gaze works - a voyeuristic fantasy about who the male editors and their readers want to be and who they want. The stylists and photographers are following a 1950s type of white, heteronormative, gendered domesticity - Jack is clothed and lounging, Alana is a scantily-clad housewife. It's so... lame.

And here we find Laura Lou Crane, fresh from her celebritising stint on the reality TV show, Love Island. In this series of images (shot by, it seems, a woman) and interview (with a man), Crane comes across as vulnerable and fragile. Alongside the images of her in small pieces of lace, PVC and ill-fitting lycra, she briefly talks about her struggle with bulimia, while at the same time highlighting the pressures that caused it - namely, the pressures of being a young woman surfing and modelling in "that industry". This is highlighted in the pull-out quotes Stab uses:

Being a surfer and traveling the world and modeling put all these pressures on me as a girl growing up in that industry. Which, don’t get me wrong, it is an amazing way to grow up, but it does weigh on you.

***

I think when Instagram and social media became huge, it was hard not to look at myself and compare it to how other girls were looking and what they were posting.

****

The reason behind this photoshoot and these photos is I want to show that yes, I have this strong body. I’m a surfer. I’m an athlete. That’s me.The questions asked of the women have changed since those days with Laura. In this interview, as in others, they're much less explicit in getting Crane to justify Stab's style and sexualisation of women, but that might be because there is a new script that women know to keep to - to talk about feeling empowered through sexualising themselves. But even when the interviews themselves focus on women's surfing lives (as did the interview with Imogen Caldwell), the images remain firmly defined by sex.

I took some screenshots of the Instagram story Stab used to promote and distribute the article. (For the record, I don't follow them.)

The contradictory links Crane makes between the impact on Instagram on her and her resulting bulimia, and then her lack of reflection on her own role in promoting sexy, feminine, idealised, female bodies on social media is, well, alarming! She clearly understands the impacts of social media on body image and mental health, and yet, because she feels as though she's come through it, she makes no attempt to protect anyone else from the same pressures.

Her body, her choice. But don't expect me to respect her choice.

IV. The legacies of empowerment

If empowerment is donning lacy lingerie and gazing doe-eyed into a camera so I can feel beautiful in European, heterosexual men's terms and for my own financial gain, then I'm out. If empowerment is going on a reality TV show that belittles and demeans me, then no, I will look for other options. If women's empowerment is defined by Stab, then I don't want a bar of it.But here it is - empowerment - apparently being taken up by the many folk commenting on Crane's Instagram post about the interview (you can find the post and comments here):

Commenters focus on this story as inspiring and empowering and on Crane as a role model for young people, especially young women and men. Her body is discussed at length as both a recovered bulimic body and a sexy body, and is celebrated for being "sporty" and "different" than super thin models. But I'm just not so sure; as I've argued before, diversity is not a white woman, and while not being thin to an emaciated degree might feel different, Crane is still slim, toned, feminine, and young - the ideal of the male gaze.

But...

While in this (very long) discussion I'm holding Crane accountable for her choices, it's still Stab that I'm repulsed by and who I'm railing against. The interview title, 'Laura Crane is empowered' is poking fun people who they know will be frustrated by the images and interview. The common rebuttals they will likely offer sit along the lines of "Don't look then", or "you're just jealous" or "femi-nazi". The idea of "don't look" is fair enough, except that it's stupid - it's online, it's available, it's part of my surfing cultural orbit. And anyway, I'm not so much concerned about me and mine as I am about the men who do look at these magazines and ogle the women on the pages, and comment on their bodies and ideas. (Although, to give them some credit, Stab didn't open the comments thread under this interview, which I was super pleased to see.)

Even worse, critics of my critique accuse me of being a bad feminist or anti-women. But I'm not. I just don't buy the idea that making money by letting faceless men take pleasure from my body is in anyway helpful to the majority of women. A couple of years ago, Hadley Freeman wrote a great article in The Guardian about changing notions of "empowerment":

The problem with this approach is that it leads to a great big pile of nothing. The suggestion that women should unthinkingly celebrate one another purely out of sisterly feeling is about as patronising as the idea that women shouldn’t trouble their brains with opinions. ... Empowerment has become the cover for doing whatever the hell you like. It is a self-created safe space: as long as you say you are empowered, anyone who complains is trying to oppress you. ... But the biggest irony about empowerment is not just how utterly meaningless – disempowered, I guess – it has become as a term, but how those who claim to feel it and those to whom it is sold are the ones who need it least. It is no surprise that I see so many adverts promising empowerment, because I am precisely the kind of person to whom empowerment is now marketed: white, thirtysomething, educated, middle class with disposable income. I don’t need to be empowered anymore than Kardashian does. Only those already in possession of quite a lot of power would feel empowered by leggings, or a TED talk, or naked selfies. Empowerment has become not only a synonym for self-indulgent narcissism, but a symbol of how identity politics can too often get distracted by those with the loudest voices and forget those most in need of it.

Freeman cites an NY Times article by Jia Tolentino, who writes that:

Sneakily, empowerment had turned into a theory that applied to the needy while describing a process more realistically applicable to the rich. The word was built on a misaligned foundation; no amount of awareness can change the fact that it’s the already-powerful who tend to experience empowerment at any meaningful rate. Today “empowerment” invokes power while signifying the lack of it. It functions like an explorer staking a claim on new territory with a white flag.

V. TL;DR: The final word

This essay is long; much, much longer than I intended when I started to write it, but there we are. It’s the product of frustration and disappointment and concern and reflection that has been going on for many years. I don't tend to write many critiques of things that happen in the surf media, mostly because there is so little that hasn't already been said well (as two examples, Holly Isemonger offers a stand-out essay, and Sophie Hellyer talks and writes on this too), so little that can be new. While there are some exceptions, and women-driven media are chief amongst them, mainstream surf media is not improving the way it treats women fast enough. It's so rare that it surprises me or excites me - it's boring. Boring and sexist. So, yeah. Usually I don't bother writing about it. But when I saw how upset some of my friends were about this interview and the images that came with it - when I saw the effects it was having - I was compelled to write my way through it.Less than 24 hours ago, when I sat down to start writing, I thought I would write a quick 500 words that would summarise what I was thinking and feeling. But it wasn't possible. And I’m not pleased about so clearly using the examples I have of specific women - I’m not usually one to do that. Instead, usually, I talk about the system in which those women are making their choices and I’ve certainly done that here too. But at the same time, with the examples I use here I couldn't avoid that the women in these images are making the choice to sexualise their own bodies and to claim it as empowerment. That’s their choice, but they’re doing it with seemingly clear knowledge of the system in which they’re making their choices, including an understanding that not all women are able to gain benefits from such practices and thus, they’re complicit in things being harder for women who don’t look like them. Not for a moment would I suggest that was their intention! But nonetheless, many girls and young women seem to look up to sexualisation and lingerie shoots as aspirational and inspirational and role models for how to make it as surfers - that is the effect.

Laura Lou Crane - and Laura Enever and Alana and all of the women I'm discussing here - deserves better than what is on offer for her via Stab. She really does. But the many people who consume the product she's presenting as empowerment deserve better too - and I include boys in that.

The main thing I learned in my PhD research about women and surfing was the politics that the women I spoke with operated by, which is rooted in a feeling of solidarity with other women and can be summarised very simply; whatever you do to get waves in the surf, don't make things harder for other women.

This is SPOT ON.

ReplyDelete[…] I am the happiest lady on earth right now, My Ex has reconcile with me.. thank you R.buckler 11 gmail……com […]

ReplyDeletetaaiheei92kks

ReplyDeletegolden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet

golden goose outlet